En varias ocasiones ya, os he llamado la atención en el blog, sobre el Blog de la HLS sobre Corporate Governance, una fuente de conocimiento gratuita y de la máxima calidad en materia de Sociedades Cotizadas, Gobierno Corporativo y Regulación Financiera, en el que publican regularmente muchas de las más reputadas autoridades americanas sobre la materia del momento. Conviene, pues, para todos los interesados en el Derecho Societario, del Mercado de Valores y Mercantil en general, echar un vistazo recurrente al mismo.

Pues bien, la entrada de ayer martes 6 de mayo bajo el título «More Than You Wanted to Know: The Failure of Mandated Disclosure», (constituye un resumen del trabajo del profesor Omri Ben-Shahar, Leo & Eileen Herzel Professor of Law at the University of Chicago Law School que podéis consultar aquí), se afronta una crítica al «disclosure» como técnica generalizada de regulación y garantía de derechos en el Derecho norteamericano, no sólo en el ámbito del Gobierno Corporativo en sentido estricto, sino también en el financiero, de seguros, responsabilidad, protección de datos, etc., de modo que se sostiene que «Mandated disclosure may be the most common and least successful regulatory technique in American law.»

El análisis parte del reconocimiento del triunfo en el sentido de su general aceptación del disclosure como mecanismo de regulación, a la vista de la experiencia legislativa americana desde la securities Acta de 1933 hasta la reciente Dodd-Frank Act, sobre la base de un fundamento último básico y de general aceptación: Las decisiones mejoran con el nivel de información del que se dispone para adoptarlas, de modo que se satisface la siguiente ecuación: menos información, peor decisión y más información, mejor decisión.

Of mandated disclosure’s triumph there is no doubt. This blog’s readers see it everywhere. Corporate scandals and financial crises ceaselessly spawn new disclosure laws: the Securities Act of 1933, the Truth-in-Lending laws of the 60s and 70s, Sarbanes-Oxley in 2002, and, recently, Dodd-Frank. Disclosure pervades tort law (“duty to warn”), consumer protection (“truth in lending”), bioethics and health care (“informed consent”), online contracting (“opportunity to read”), food law (“nutrition data”), campaign finance regulation, privacy protection, insurance regulation, and more.

This triumph is understandable. Mandated disclosure aspires to help people making complex decisions while dealing with specialists by requiring the latter (disclosers) to give the former (disclosees) information so that disclosees choose sensibly and disclosers do not abuse their position. It is seductively plausible. (Don’t people make poor decisions because they have poor information? Won’t they make good decisions with good information?) It alluringly fits all ideologies. (Thaler and Sunstein like it because it is “libertarian paternalistic”; corporations would “rather disclose than be regulated”). So mandates are enacted unopposed. Literally.

A partir de ahí, el post formula una crítica interesante al estado de la cuestión: el éxito del disclosure no guarda relación con su popularidad y difusión, dado que el primero puede considerarse limitado por dos circunstancias: el exceso y la complejidad de la información, por un lado, y la acumulación de «disclosures» en la toma de decisiones por otro.

Mandated disclosure’s failure is no stranger than its popularity. Disclosures are the fine print everybody derides, the interminable terms everybody clicks agreement to without reading. Disclosures describe complex facts in complex language; most people little like the former and little understand the latter. Decisions requiring sophistication and expertise cannot be bettered by pelting the unsophisticated and inexpert with data.

If disclosure could work, it would be working now. In area after area, able people have ingeniously tried method after method. Full and summary disclosure, advance and real-time disclosure, oral and written disclosure, disclosure in words and in numbers, disclosure in boxes and in charts, disclosure in depth and in scores, disclosure by guidelines and by formulas, disclosure in print and on line. But success remains around the corner.

Today, sophisticated “disclosurites” want simplification, often guided by behavioral economics. But decades of simplification have yielded little progress. And behavioral economics is not the solution, it is the explanation for the failure. It reveals people perceiving and processing information in so many distorting ways that no mandate can account for them all. For example, studies of conflict-of-interest disclosure show that people’s “heuristics and biases” are so unpredictable that designing disclosure to overcome one bias can just trigger another.

In some markets, “information intermediaries” digest complex information and disseminate advice. But intermediaries, when present and reliable, are largely substitutes for, not complements to, mandated disclosure. Nor do they need it for their work.

It is often recognized that mandated disclosure fails because of the “overload problem.” But mandated disclosure is also defeated by the “accumulation problem.” People face not only a clutter of information in each disclosure, they face a clutter across disclosures. When disclosures come single spies, they may be manageable; in battalions they are not. So the accumulation problem arises because disclosees confront so many disclosures daily and so many consequential disclosures yearly that they could not attend to (much less master) more than a few even if they wanted to.

The accumulation problem defeats even sophisticated regulators, faithful to the best methods of cost benefit analysis (CBA), and keen to solve overload problems. Assume that disclosure regulations can be subject to meaningful CBA—although John Coates, in a paper discussed on the Forum here, argues convincingly that it cannot. Regulators have neither the tools nor the insight to design new disclosures that resolve the accumulation problem.

Concluyo tomando del texto una interesante definición del disclosure obligatorio como técnica de regulación:

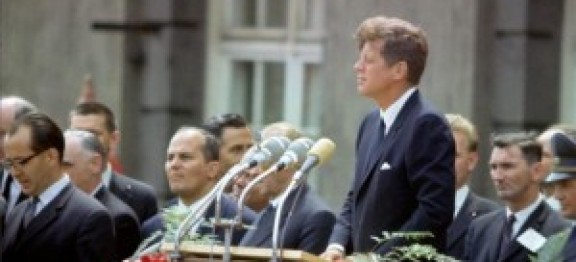

…mandated disclosure is like Kennedy after the Bay of Pigs: “The worse I do, the more popular I get.” Or like Dr. Johnson’s description of second marriages: “the triumph of hope over experience.” For disclosure does not work, cannot be fixed, and can do more harm than good. It has failed time after time, in place after place in area after area, in method after method, in decade after decade.